For the last three months we have been travelling through the wild, rugged deserts and impenetrable cloud forests of north western Argentina, but now it was time to leave.

We did so by climbing the circuitous road from Mendoza towards the border with Chile. As soon as we started to descend the western side of the mighty Andes, it was immediately clear we were entering a completely different floristic region; dry arid lands were replaced by forests and streams. The hot dusty desert air had parched and dried our skin, we longed to be at the ocean.

Heading west as quickly as we could, around the northern suburbs of Santiago and crossing the fertile central valley of this thin country, we encountered the mountains that skirt coastal Chile. From their summit the deep blue of the Pacific beckoned.

Following the Rapel river valley we approached the sea near to the village of Navidad and found a small marsh.

La laguna en Navidad

– over which circled a shower of ‘snowflakes’, nesting egrets.

Garzas boyeras, Garcitas bueyeras, Cattle Egrets

Better still, this tiny marsh was the home to a flotilla of Black-necked Swans.

Cisnes de cuello negro , Black-necked Swans

We decided to camp here at the marsh, the ocean would have to wait a little longer.

Nuestro camping en Navidad

The marsh was fringed by a dense margin of rushes but we found one small spot that cattle used to come to drink, here we set up a hide.

Nuestro observatorio para sacar fotos

As we slept at night we could hear the distant rollers pounding the cliffs but on this Chilean marsh we found peace and prolific wildlife.

For three days we watched, through the rushes, as the birds left the marsh in the morning to feed on the estuary and then return in the afternoon to feed their young.

Cisnes de cuello negro, Black-necked Swans.

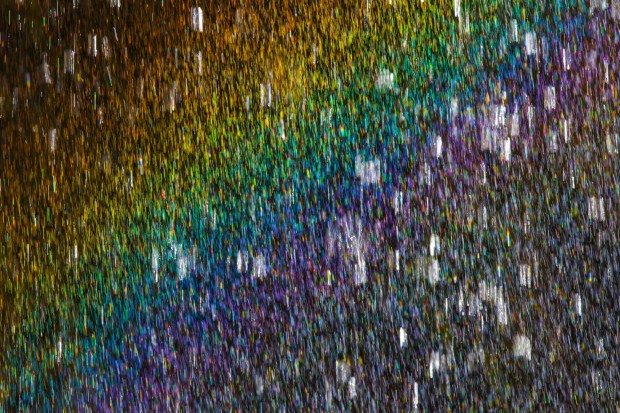

Sitting silently, unseen in a hide, keeps you in a constant state of expectant suspense. Marsh sounds are weird, there are croaks, groans, high pitched squeals, sploshes and whooshes. Sometimes there is nothing to watch except the mesmeric reflections in the water.

Los reflejos de los juncos en el agua

But the life in a marsh is a vibrant one.

Pato real, Pato overo, Chiloe Wigeon.

Constantly peering through the vertical lines of the rushes, imagination turns to reality as its inhabitants appear and disappear.

Drifting

Crias de Cisne de cuello negro, Black-necked Swan cygnets.

Swimming –

Coipo crias estan jugando, Coypu youngsters playing.

Creeping –

Tagua de frente roja, Gallareta escudete rojo, Red-fronted Coot

Fishing –

Huiravillo, Mirasol comun, Striped-backed Bittern.

Balancing –

Trabajador, Junquero, Wren-like Rushbird.

And cavorting –

Siete colores , Tachuri siete colores, Many-coloured Rush-tyrant.

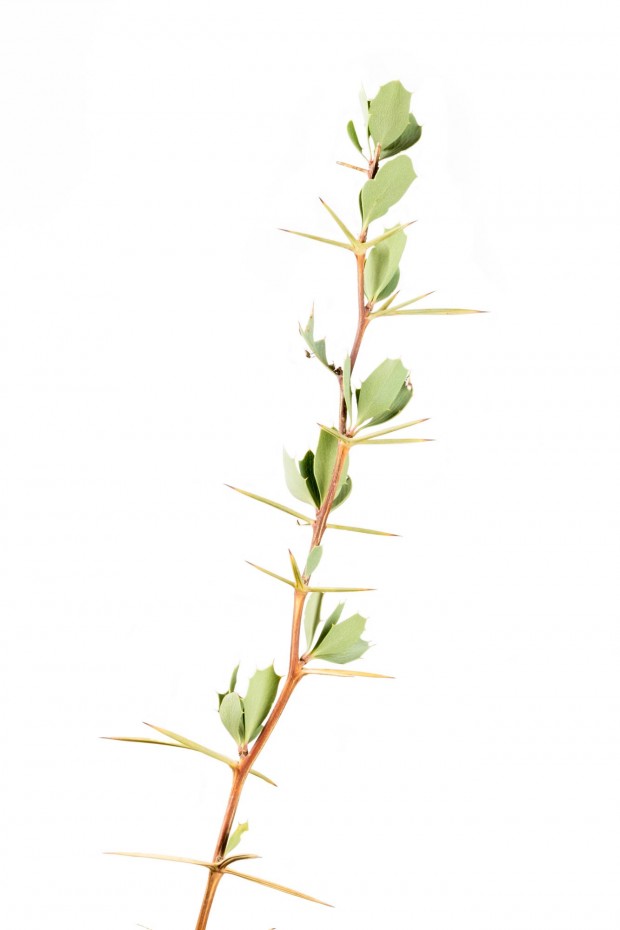

A few days previously a birdwatcher had said to us that all the birds in Chile were brown and uninteresting. What would he have said had he spent a few hours overlooking this marsh?

What would he have said if he had seen an adult Many-coloured Rush Tyrant ? This tiny reclusive denizen of the rushes would stand up proud in any competition as ‘the most colourful bird in South America’. In Chile it is called ‘siete colores’, the seven colours!

Siete colores, adulto, Tachuri siete-colores,

Adult Many-coloured Rush-Tyrant.