On August 28th 2015 Paula and I returned to South America from the UK. The Andean Wildlife Project resumes and our objective from now on will be more ornithological and in particular to understand why there are so many bird species on this incredible continent.

Where best to start this quest than to head for one of the most avian rich countries in the world, Peru. To get there we needed to drive right across Argentina, traverse the Andes mountains and then up through the Atacama desert in Chile and finally to cross the border of Peru at Arica. Birding across South America.

We left Buenos Aires and headed north following the flat marshlands of the Parana river. This massive series of wetlands is now much reduced, replaced instead by cattle ranching country. Nevertheless a variety of Egrets, Ibis, Wood Rails and Snail Kites abounded.

Moving east we entered the Chaco ecoregion. We found that much of the land was degraded and much used as cattle pasture. Eventually we found a series of sand tracks that penetrated the almost impenetrable thorny scrub, interspersed with candelabra cacti and small low growing acacia type trees. In this area we found Black-crested Finch, Golden-billed Saltators , Duica Finches and Monk Parakeets.

The journey northwards from Cordoba to Tucuman took us into an altogether richer agricultural area, where great machines were harvesting the sugar cane. Picui ground doves swarmed over the plantations and Guira Cuckoos, usually in small groups, were common. To our west we saw tantalising glimpses of the Andean foothills and longed to reach those verdant valleys where we had spent so many happy hours earlier in the year. The nearer we got to Tucuman so the Lemon groves increased, trucks piled high with the fruit vied with the even larger trucks carrying sugar cane.

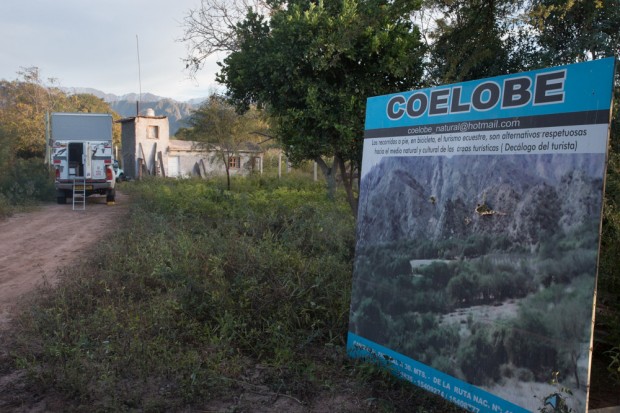

We spent a day with our good friends in Tucuman and also had some necessary minor repairs done to the vehicle, putting new rivets in the steps, which had vibrated out on the poor roads.

Still further north of Salta, passing alongside the transitional forests on the foothills, White-tailed and Roadside hawks were regularly perched on the larger trees and high above circled Turkey Vultures and the occasional Aguila mora. We passed the turnoff to El Rey National Park; a place we had not visited and wanted to in the future, but our destination in deepest, darkest Peru remained a long way off, we needed to press on.

On Tuesday September 1st we started our climb into the high Andes, into the beautiful Puna ecoregion where stipa grasses dominated and the few small wetlands held resident Crested Ducks.

We reached the Jama Pass in the late afternoon only to find the border closed. We spent a fitful night’s sleep in the freezing cold and at an uncomfortable altitude of 4500m.

Crossing the border the next day we climbed even higher onto the Chilean altiplano, an arrestingly stark and barren environment.

We dropped down the western slope of the Andes into San Pedro de Atacama and continued onwards across the Atacama desert and eventually to the Chilean coast at Paposo. We had visited this area eight months prior and were interested to find if the heavy rains that had occurred after we left had led to a rare flowering of the coastal desert. There were many small shrubs that were in flower and certainly everything was much greener, but the spectacular flowering of the bulbous plants had not yet started.

We camped on the shore and were surprised by the number of Snowy Plovers and Seaside Cinclodes.

Spending more time on the beautiful Chilean coast would have to wait for another time, we had to move on .